Maya, and self-intersecting nurbsCurves

Aug 9, 2010This is a story about my journey in solving a problem at work involving curves. The solution seemed really simple at first, but because of a stupid Maya issue, this turned into me having to rewrite the tool 3 times before I discovered a surprising solution.

The Problem:

Because we rely heavily on the process of importing Illustrator .ai files into Maya as nurbsCurves, we constantly have to deal with curves that intersect themselves. This is a result of the curves having been hand drawn originally in the art department, and they posed issues during rendering after being planar-ized.

We needed a way to detect self-intersecting nurbsCurves, so that we could fix them before working with them as nurbsSurfaces.

Getting started. I hate you, Maya:

The obvious place for me to start was to use the existing curveIntersect command. This command will tell you if two curves intersect, and at what points. Although it requires that you tell it 2 individual curves to test, I figured I could just split the single curve into parts (using detach curve), and pair off all the parts to test them. And here is where I ran into something that just pissed me off. While it works great to tell you where the intersection is… when it DOESN’T find an intersection, it prints a “Warning: Could not find curve-curve intersection” line. Printing to the script editor in maya is SUPER expensive as I have found. Everything slows down. This was the initial reason I decided not to use this method. I later found out the RIGHT hack way to deal with this is to wrap the entire process in scriptEditorInfo commands to suppress warnings being printed to the Script Editor and re-enable after. This method does prevent the amazing slowness, but still has the unacceptable flood of warnings once suppression is turned back off again. So even with this fix, I still found this approach to be too slow. For a single complex curve object that might have, say, 500 spans… that would be 124750 unique combinations that would have to be tested with the curveIntersect command. In a test of just looping that many times and calling this command, the process took 54 seconds! No way could this work, with a scene that could easily have 2000+ nurbsCurves!

Great. Now I get to investigate my own intersection detection from scratch.

Approach #2 – Brute Force

I’m a film school graduate… not a computer science major. Never thought I would have to use the kind of math I TRIED to implement for a first solution. Solving the cubic function of every curve segment to find the intersections? Meh. Too hard.

Next I thought of an idea to take a curve and sample N-amount of points from start to end parameter. So lets say 1000 samples. I would get 1000 points on the curve, then compare each point to the other non-neighboring points to see if they are within a distance tolerance of each other. If they are, I consider this a point in the curve where it looped and self-intersected. This method did work. It was still not super fast, but no where NEAR as slow as using the intersect command. I built in some dynamic scaling of the sampling and tolerance to accommodate for curves of different size and complexity. Even though I had to test 499500 point combinations per nurbsCurve for the 1000 point samples, this was only math and not a repeat call to curveIntersect. Ultimately, I was still not where I needed to be in terms of usability. A complex curve could still be a few seconds to test. Still too slow.

Approach #2.5 – Brute Force mixed with a fast little pre-check

Amongst the tons of search results I waded through on google, I found a really cool little trick someone came up with: http://forums.cgsociety.org/archive/index.php/t-517347.html

He suggested a cool hack where you planar the surface, then convert it to polygon with certain options, and then count the number of resulting faces that were produced. Theoretically there should only be 1 face if the curve never intersected itself. If it did, those loops should also have faces.

Well then, why couldn’t I just use this method as my detection algorithm? While it was pretty darn fast since no iteration is involved, I discovered a few limited cases where I was getting False Negatives: The method said there was only one face (no intersection) on a curve that actually did have a self intersection. So I decided to use this as a pre-check to save time. If it DID say there was self-intersection, great! Log it. Otherwise, slow test it with the brute force method.

Approach #3 – Math that I never learned

At this point I had accepted the solution for detecting self-intersection, and moved on to writing a maya UI for the tool. It would detect loops and optionally even report back the best estimate to the point where it actually occurred. But once I started writing another bigger tool that would use this script, I just knew it could be done faster with the power of math and without the poop of maya script command calls.

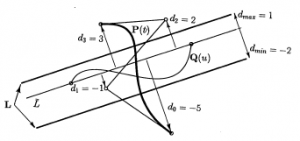

I discovered a paper written about a method called “Bezier Clipping” : Curve intersection using Bezier Clipping

For this method to be used on a single curve, one would first need to split the curve into its segments, in my case producing a bunch of cubic curves. With each pair of combinations, a bounding box check would be performed. If the bounding boxes do not overlap, you are done. No intersection would have occurred. If the bounding boxes did overlap, then you would start drilling down the check by clipping away sections of the curves outside the bounding box overlap. You can discover the intersection pretty fast by either drilling down until the segments are small enough to represent the single point, or the segments are now small enough to be considered linear and a you can use the slopes to find the intersection.

I was really stoked by this idea. The paper made it look really straight forward. I ended up writing a really cool custom wrapper around a nurbsCurve object that could represent a sub-section of the curve, and could easily give me things like the length and parameter range. It had a split() method that could split the curve at a given length or parameter and give me back two sub-curves, of which each could further be split. This class was integrated into the Bezier Clipping method and I finally got it all working. The initial tests were amazingly fast, but I ended up finding that the process became quite slow on large numbers of complex curves. I attribute this to my implementation of the bezier clipping, not the method itself. I didn’t take the time to actually generate proper sub-segments based on the bounding box overlap, and instead just did a simple 50/50 split of each curve, and tested the new combinations. I think I was just so bummed about the performance results that I didn’t feel like making the improvements to the process would make enough of a difference. What I had now was ultimately slower than my brute force method when tested against an entire scene of curves. So I decided to just go back to that.

Approach #4 – The unexpected trick

Whilst working on the larger project meant to make use of the loop detection script, I discovered something amongst the curve commands. offsetCurve includes the function of clipping away loops while creating the new offset curve object. My idea was to create an offsetCurve with the minimal changes, at a zero distance, so the curves would be right on top of each other. Then I could just compare the area/length/etc attributes of the curves to see if there was a change. This was really fast and really accurate, down to the smallest loops. Right now I’m comparing the area and length values rounded to a certain tolerance. This method was amazingly fast, and a fraction of the code.

The only minor downside was I found that because of the rounding I needed to do to compare the values, every so often a couple curves would be found as self-intersecting when they were not. Thats much better than MISSING curves during the detection. So what I did was combine the earlier face-counting solution with this one, to fail over between the two. The combination was really fast and accurate, without 100,000 warnings showing up in the stupid script editor.

All in all

I’m really surprised how many versions of this tool I had to write, to ultimately end up at a really simple one. I never would have thought to look at this offsetCurve command for a solution. Had to dig into some math I never thought I would use, also. So THATS what those stupid polynomial equations were for?